Participant dropout is a potential source of bias in longitudinal studies. However, Bell (2013) showed differential dropout doesn’t always bias results, and sometimes non-differential dropout does bias results. The solution in all cases is a mixed model. Bell demonstrated this with a simulation using a fictional data set. Bell created 10,000 data sets with perturbations meant to simulate between-person and within-person effects. I created 100 data sets to explore the paper for this post.

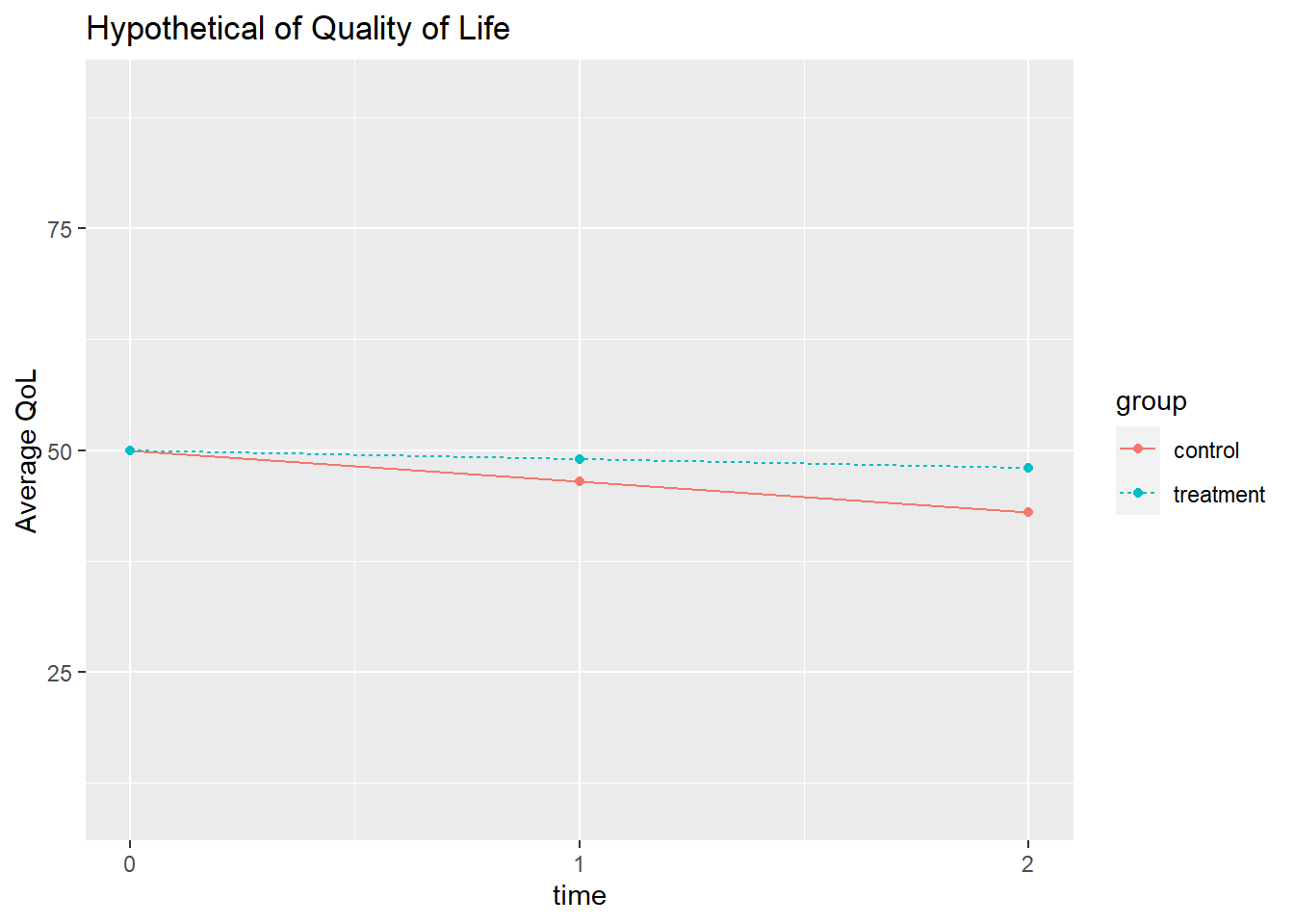

Suppose a clinical trial assesses quality of life (QoL) at three time points (0, 1, and 2) for n = 200 participants with a degenerative disease. The participants are divided into a treatment and placebo group. All participants start with a QoL of 50 at time = 0. Their QoL degrades as the disease progresses. Some participants in each group drop out of the study, potentially at different rates and for different reasons. The process might look like this.

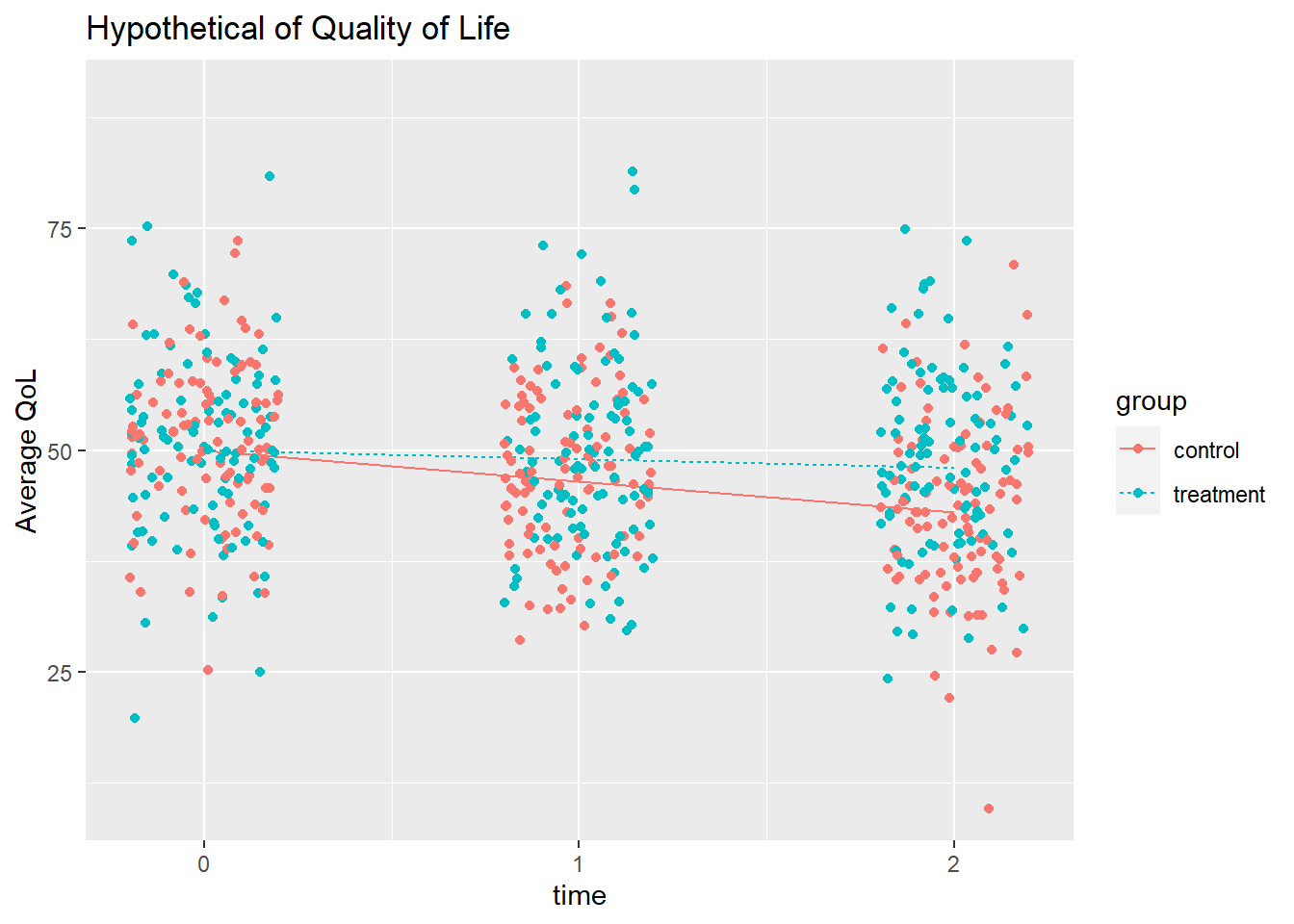

Bell perturbed the data generating process that produced the two time series above by adding random values from a normal distribution. Bell created between-person effects by adding the same value to each time stage for a person, and within-person effects by applying a different value at each time stage.

Here’s how a the 100 perturbations might look for a control and a treatment participant.

Missing data can be classified as

- Missing completely at random (MCAR). Dropout is unrelated to the covariates or to the prior values, so there are no systematic group differences.

- Missing at random (MAR). Dropout is not random, but you can measure and control for its causes, so the remaining dropout is random.

- Missing not at random (MNAR). Dropout is not random, and you cannot control its causes.

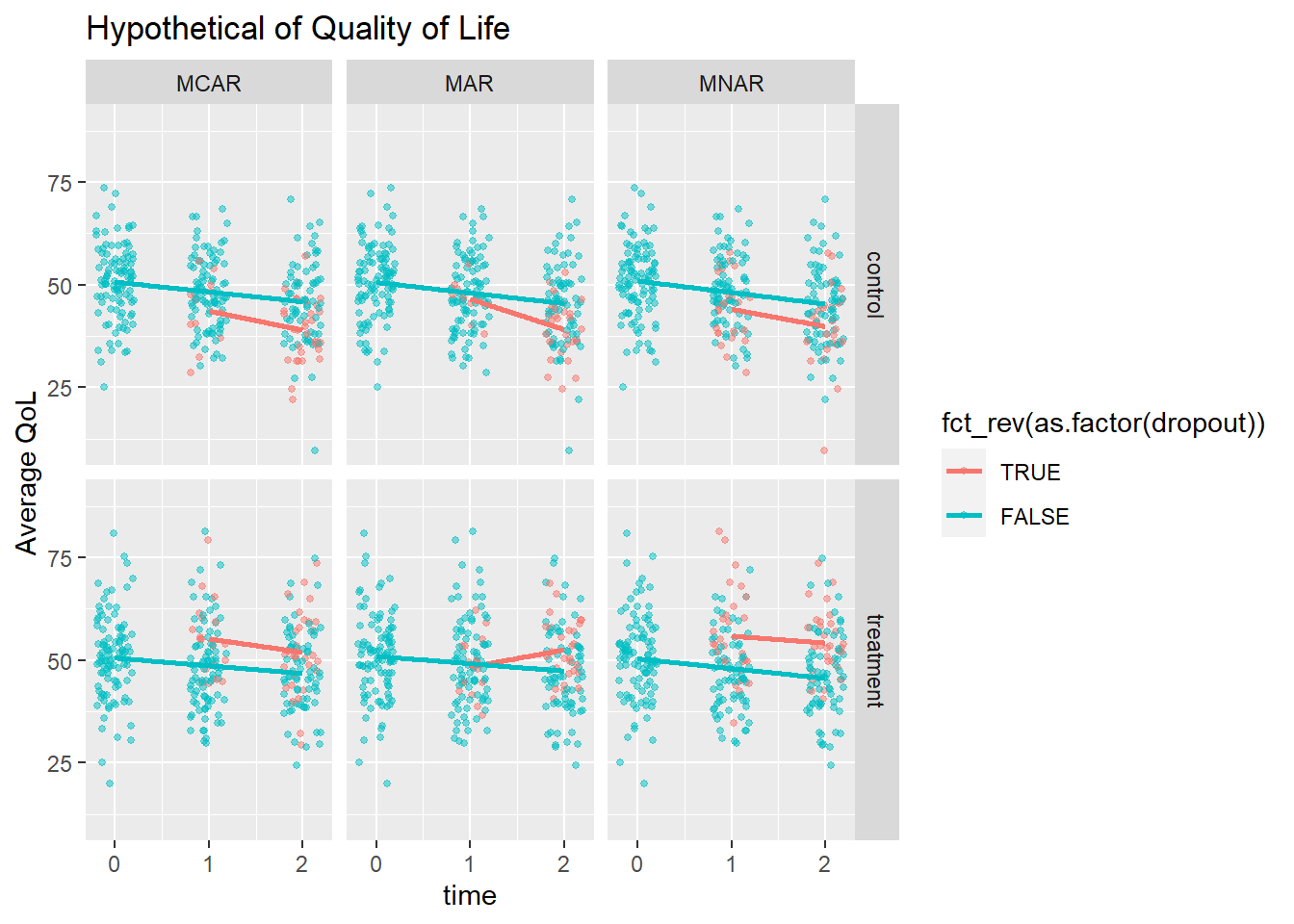

Dropout is MCAR if the participant drops out of a study for reasons having nothing to do with the study. Otherwise, it’s MAR or MNAR. You can detect MCAR by comparing the dropouts’ and completers’ measurements. MCAR will have similar starting values and progressions (slopes).

Researchers sometimes handle missingness by only considering complete cases, or imputing with the last observed value carried forward (LOCF) or mean value, but these methods introduce bias. If your data is MCAR or MAR, likelihood based mixed models for repeated measures can yield unbiased estimates of the treatment effect. These models use information from participants with complete data to implicitly impute the missing values.

Demonstation with Simulations

Bell simulated MCAR, MAR, and MNAR by removing data points from the simulation data sets in two ways: by dropout rate (equal vs differing) between the control and treatment group, and by direction in response to QoL (same vs opposite). There are four combinations of the causes. Three missingness reasons times four patterns equals twelve simulations, each repeated 10,000 times (100 for me).

MCAR

- Rate. Equal rates (30%) for each group, or differing rates (control = 40%, treatment = 20%).

- Direction. Same response to a low QoL at lag-1 time (low relative to the overall avg at lag-1 time), or different response (control more likely to drop out if < avg, treatment more likely if > avg).

MAR

- Rate. Equal rates (30%) for each group, but dependent on QoL relative to the group average at the lag-1 time, or differing rates (40%/20%).

- Direction. Same or different response, but dependent on the group average.

MNAR

- Same as MAR, but comparing the current QoL to the group average at lag-1 time instead.

Here is what MCAR, MAR, and MNAR might look like for those two participants above.

Simulation Analysis

Bell fit a linear regression model of QoL ~ group * time for each simulated data set. In my case, that comes to 4 variations of direction and rate * 4 modeling approaches * 3 missingness types * 100 sims = 4,800 model fits. For each fit, augment the data set with the fitted values. Then calculate the average fitted value at time = 2 across the 100 simulations, and compare it to the average actual value. Bias is the percent difference between the measured and actual.

The results are shown in the table below. The my measured bias differs a lot from Bell in magnitude, but the mixed model agrees in its improvement on bias.

|

Equal 30% |

20% treat, 40% ctrl |

Equal 30% |

20% treat, 40% ctrl |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCAR | ||||

| Complete case | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Mean imputation | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| LOCF | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Mixed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MAR | ||||

| Complete case | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Mean imputation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| LOCF | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Mixed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MNAR | ||||

| Complete case | 6 | 6 | 0 | 2 |

| Mean imputation | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| LOCF | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Mixed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Conclusion

Participant dropout can bias results, but not necessarily. Imputation or taking complete cases is not a viable option for handling participant dropout. The safest approach is to used a mixed model.

References

Bell, M. L., Kenward, M. G., Fairclough, D. L., & Horton, N. J. (2013). Differential dropout and bias in randomised controlled trials: when it matters and when it may not. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 346, e8668. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8668. html.